Language Corpora – Copyright – Data Protection: The Legal Point of View

Felix Zimmermann1, Timm Lehmberg2

Hannover University – Institute for Legal Informatics1

Königsworther Platz 1, 30167 Hannover, Germany

Hamburg University – SFB 538: Multilingualism2

Max-Brauer-Allee 60, 22765 Hamburg, Germany

Corresponding author: timm.lehmberg@uni-hamburg.de

1 Introduction

Creating comprehensive and sustainable archives of linguistic data and making

them (or parts of them) accessible to the research community leads to a number

of essential legal questions being raised by different aspects of law. Like

any discipline handling large amounts of data, the digital humanities are

confronted with a complex system of authorities and restrictions. From

acquisition, through storing and processing to the annotation and finally

publication of the data, there are a number of rights as well as duties each

participant in this process has to consider. Additionally, some legal systems

provide special rules for the use of data for scientific purposes. On the one

hand the opacity of the legal position leads to the assumption that, in many

cases, linguistic data are used and transferred in a way that does not comply

with legal requirements. On the other hand there is a noticeable tendency not

to transfer linguistic data for fear of breaking the law (see Jüttner 2000

[1], and Patzelt 2003 [3]).

2 Relevant Areas of Law

Two different areas of law play an important role in the use of linguistic

data for research purposes:

- "Intellectual Property Rights" provide legal protection of

non-material goods which are any kind of intellectual property of a third

party. This includes, amongst others, literary works as well as databases,

software and utility patents. In terms of law language corpora are defined

as databases.

- "Privacy and Personal Data Protection Law" imposes restrictions

for the processing of any personal data, i.e., any data that can be linked

to an individual. In the face of linguistic data processing any audio and

video recordings (and their transcriptions) as well as metadata that contain

personal information on speakers are covered by this law.

Both areas are relevant to the complete process of data processing and have to

be considered from the initial step of the data based work (normally the

acquisition of the data) to the time of publication.

3 Aspects of National and International Law

In everyday legal practice a particularly relevant role is played by those

legislative rulesets that are based on constitutional norms. Within these,

interests and entitlements of other involved individuals and institutions,

which are worthy of protection, are often outlined in minute detail in

relation to the procurement, processing, and transfer of linguistic primary

data.

Federal states, which contain individual member states with their own

legislative authority (such as the US, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Spain)

may have enacted specific member state rules. This leads to the possibility

that there may be complex and potentially internally conflicting legislation

within a state in a federation.

It is not just, however, the original national legal situation which regulates

the use of linguistic data. International obligations may, through direct or

indirect applicability, have considerable impact. In 2007, 27 member states of

the European Union adhere to European legal instruments (such as directives

and regulations) in relation to the national and international use of data.

Pursuant to the doctrine of direct applicability enshrined in Article 10

of the Treaty establishing the European Communities, these norms have priority

in relation to potentially conflicting national norms. What needs to be borne

in mind is that the individual member states have some leeway in the

implementation of the instruments, which may lead to minute differences in the

level of protection.

Finally, public international treaties which oblige their signatories to

adhere to certain minimal standards need to be taken into consideration. In

relation to linguistic data and the problem of copyright, the Copyright

Treaty of the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO, 1996) is to

be considered as particularly relevant. The question of personality rights

with a view to individuals whose data are processed is addressed in the

Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (1950).

Additionally, the Convention for the Protection of Individuals with

regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data (1981) provides further

normative guidance for the member states of the European Union.

4 The Legal Impact of Intellectual Property

Copyright protection of language corpora is provided by different aspects of

applicable law. In order to simplify the presentation, there will be a focus

on the law of harmonised rules by the European Communities that are placed

within the framework of the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO).

4.1 Directive 91/250/EC on the Legal Protection of Computer Programs

The different tasks of linguistic data processing (transcription as well as

annotation etc.) require a considerable number of software tools. For this

purpose, apart from commercial development, software is written by the

research establishment's employees. The participants in this process rarely

bother with legal protection of their work. By implementing the Directive

91/250/EC, computer programs in all Member States of the European Community

are protected by copyright law. In accordance with Article 1.3 of the

Directive 91/250/EC, a computer program is protected, if it is original in the

sense that it is the author's own intellectual creation. Ideas and principles

of a computer program are not protected by this Directive. The term of

protection is the author's lifetime plus a period of 50 years. The author owns

the exclusive rights to reproduce, translate, adapt and publicly distribute

his computer program.

If a computer program has been created by an employee, in accordance with

Article 2.3 of the Directive 91/250/EC, the employer is, unless otherwise

provided by contract, the copyright holder of the resource. In the case of

software being developed within a research project, from this point of view

the copyright is held by the respective research establishment (University

etc.).

4.2 Directive 96/9/EC on the Legal Protection of Databases

In accordance with Article 1.2 of the Directive 96/9/EC, a database is defined

as a "collection of independent works, data or other materials arranged in a

systematic or methodical way and individually accessible by electronic or

other means". Without exception, linguistic corpus data come under this

protection. This Directive makes two significant stipulations. First, it

offers protection by copyright to databases which, by reason of the selection

or arrangement of their contents, constitute the author's own intellectual

creation. Thereby the author owns the exclusive right to carry out or

authorise the reproduction, alteration and distribution. Secondly the

Directive creates an exclusive right protection sui generis for makers

of databases, independent of the degree of innovation. This protection of any

investment allows the makers of databases to prevent unauthorised extraction

and/or re-utilisation.

4.3 Copyright Directive 2001/29/EC

The Copyright Directive 2001/29/EC adapts legislation on copyright and related

rights to reflect technological developments into European Community law. In

this process, it discusses and harmonises the property of reproduction,

communication and distribution rights. Concerning linguistic research data,

attention should be paid to Article 5.3(a) of the Copyright Directive. It

gives freedom to Member States in supporting non-commercial science by making

copyright less restrictive for academic use of copyrighted work.

5 The Legal Impact of Data Protection

Directive 95/46/EC on the protection of

individuals with regard to the processing of personal data imposes strict

restrictions for the elevation and utilisation of personal data. Personal data

are pieces of information which can be linked to a specific person. The

processing of personal data only is permitted by law, if there is a clear and

lawful purpose at the time of data procurement, and if the respective person

has expressed his/her consent. Further restrictions are imposed, if the

racial, national or ethnical origin, political opinion, religious or

philosophical beliefs are apparent. The same applies to the disclosure of

health conditions or sexual life. If personal data are transferred to

countries outside of the European Union (Transborder Dataflow to third

countries), a level of protection has to be guaranteed that is equivalent to

the European level, for example by means of the

Safe-Harbour-Principles. The respective person may enforce his/her

rights by means such as disclosure and deletion of the data. Article 6.2,

Article 11.2 and Article 13.2 of the Data Protection Directive contain

privileges for academic research. An escape strategy in respect of data

protection law problems is complete anonymisation (disguising by removing

personal information by abbreviating names, locations etc.) or

pseudonymisation (disguising by aliasing individuals, locations, etc.) of the

personal data. However, it remains unsolved which level of abstraction

constitutes sufficient anonymisation, particularly if it is possible to draw

conclusions by joining the data with other resources.

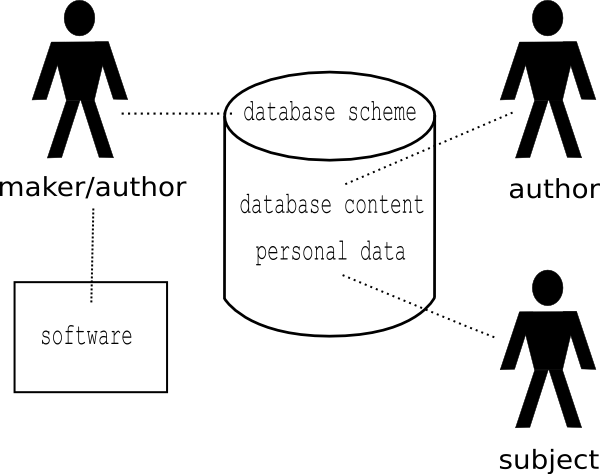

Figure 1 gives an overview about the different types of right holders

to a database.

Figure 1: The different types of right holders

Figure 1: The different types of right holders

6 Legal Competence by Trusted Third Parties

An additional option is given by the use of a trusted third party hosting the

information that has been disguised by anonymisation or pseudonymisation. It

may act as a trustee, passing the aliased or anonymised data from its origin

to a requesting research institution. The trusted party is not required by

law, but it has the ability to provide a high level of data security,

integrity and protection during the whole data transaction process (Kilian et

al 1995, p. 63 [2]). Additionally a trusted party can provide

specialist advice in technical and copyright matters. Further, we suggest

proceedings to increase legal certainty in case of creating and using

linguistic databases.

References

- [1]

-

Irmtraud Jüttner.

Mannheimer Korpus und Urheberrecht. Die Einbeziehung

zeitgenössischer digitalisierter Texte in die computergespeicherten

Korpora des IDS und ihre juristischen Grundlagen.

Sprachreport, 3:11-13, 2000.

- [2]

-

Wolfgang Kilian.

Daten für die Forschung im Gesundheitswesen, chapter 4.

Gutachten II, pages 57-76.

Toeche-Mittler Verlag, 1995.

- [3]

-

Johannes Patzelt.

Unter juristischem Blickwinkel: Textkorpora und Urheberrecht.

In Werner Wegstein Johannes Schwitalla, editor, Korpuslinguistik

deutsch: synchron – diachron – kontrastiv: Würzburger Kolloqium 2003,

Würzburg, 2003.