Project B10:

Tense and Temporal Adverbials in Extensional and Intensional Contexts

Tense and Temporal Adverbials in Extensional and Intensional Contexts

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

Aims

A Theoretical Research

A.1 A Theory of the Perfect

Perfect constructions will also receive particular emphasis in the research of the project in the ensuing phase of the project. They provide the most productive material with which to test and develop the morpho-semantic architecture of the project. As part of the project, there is a sizable publication on this range of topics in preparation, due to be published by de Gruyter.

The so-called perfect is a "tense" whose analysis is hotly debated in the literature. (Herweg, 1990) analyses the perfect as a relation between two events; the perfect introduces an "orientating event". For (Kamp and Reyle, 1993), the perfect expresses the state after the culminataion point of an accomplishment/achievement. For (Musan, 2000), the perfect introduces a "perfect time" that can extend up to the reference time (her "tense time"). This project maintains the view that "perfect" is a purely descriptive category that a variety of constructions fall into. Furthermore, even one and the same "perfect form" often has to be interpreted in semantically differing ways. This will now be demonstrated.

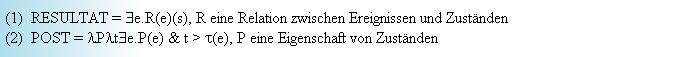

Resultative perfects: (Kratzer, 1994, Kratzer, 1996), (Stechow, 1996), (Rapp, 1998b), (Rapp and Stechow, 2000) specify for the adjectival passive a single operator that indicates a lexically characterised POST-state. (Kratzer, 2000) indicates a second result operator that delivers a time after the VP event, similar to Klein's (1994) POST-time operator. The adverb still disambiguates the two readings (cf. (Nedjalkov, 1988)). The two result operators are these:

According to (Kratzer, 2000), the choice of the correct result operator depends on the Aktionsart, i.e. on the logical type of the embedded VP.

"Adjectival passive" (Kratzer, 2000)

(3) a. Das Geschäft ist immer noch geöffnet (TARGET

state)

The shop is

always still opened

"The shop is still

open."

b. *Der Aufsatz ist

immer noch abgegeben (POST-time)

The

essay is always still handed-in

"*The essay is still handed in."

The contrast follows if öffnen ("open") is a relation between events and abgeben ("hand in") a feature of events (see "Theorie der Aktionsarten"). The operator RESULT can also assist in the analysis of

(4) Karl ist (?noch immer) vom Stuhl

gefallen (Wunderlich, 1970: 142 f.)

Karl has

(?still always) from-the chair fallen

"Karl has

(?still) fallen off the chair."

Cf. here the discussion in (Herweg, 1990: 182).

In German, indication of the agent is incompatible with an adjectival passive (cf. (Rapp, 1997)):

(5) Die Wiese ist seit drei Tagen (*von Ede) gemäht

The meadow is since three days

(*by Ede) mown

"The meadow has been mown (*by Ede) for three days."

Comparison with modern Greek shows that this option is dependent on the parameters of the individual language.

(6) mod. Gr. OkTo vivlio ine grameno

apo ti Maria (Anagnostopoulou, 2001)

The book is

written by Maria

According to Anagnostopoulou, the difference can be syntactically explained via application of the result operator below Kratzer's (1994) VoiceP in German but above it in modern Greek.

XN perfect: The following contrast, observed in (Bäuerle, 1979: 77), shows that there must also be a resultative haben ("have") perfect in German.

(7) a. Seit einer Stunde hat er die Jacke

ausgezogen (resultative)

Since one hour

has he the jacket taken-off

"He took off his

jacket an hour ago and hasn't had it on since."

b. Ich habe ihn

seit einer Stunde beobachtet

I have him since one

hour observed

"I have observed him for an

hour."

The second sentence is an "up-to-now" perfect as defined by (Schipporeit, 1971) - although the analysis is controversial. The english parallel

(8) Mary has lived in Amsterdam since 1987

is presumably analysed such that the durative adverbial "since 1987" specifies the beginning of an "extended now" perfect (XN perfect) in the sense in which this term is used by (Pickbourn, 1798), (McCoard, 1978), (Dowty, 1979) or (Iatridou and Izvorski, 1998). Thus, the XN perfect is a further possible reading for the perfect. In (Stechow, 2001b), (Musan, 2000) and (Musan, 2001), it is argued that German has to be analysed differently, in view of the similarity in meaning of example (8b) and

(9) Ich beobachte ihn seit einer Stunde

I observe him since

one hour

"I have been observing him

for an hour."

Anteriority perfect: According to (Musan, 2000), the German haben ("have") perfect introduces a past time that can extend to the reference time. Following Musan, one can call this reading the -reading of the perfect. While Musan thinks that all perfect readings can be reduced to this variant, in this project it is argued that this is not possible. As a special case of the -perfect, we have preterite uses.

(10) Franziska hat mich vor zwei Stunden

angerufen (Glinz, 1968)

Franziska has me ago two hours phoned

"Franziska phoned me two hours ago."

In this sentence, the temporal adverbial localises the event time. In contrast to the German past tense, the ?-perfect is a relative tense (cf. (Katz and Arosio, 2001)):

(12) Nächsten Monat bezahle ich alle Rechnungen, die bis

dahin eingegangen sind/*eingingen.

Next month pay I all bills,

which until then arrived have/*arrived

"Next month I will pay all

the bills that have arrived/*arrived by then."

Cf. here the following example, which shows that POST can be realised by the simple past:

(11) a. I will answer every email that arrived (Abusch, 1996)

b. ? Ich werde jede Mail beantworten, die ankam

I will every email answer, which arrived

"? I will answer every email that arrived."

c. = Ich werde jede Mail beantworten, die angekommen ist

I will every email answer, which arrived has

d. = "I will answer every email that has arrived."

The morphology fuses different atoms of meaning at different times, and it does so with the same morphology in different ways. Evidence for this is the attributive participle in German.

(12) a. Die vor drei

Tagen (von Ede) gemähte

Wiese (passive +

perfect)

The ago three days (by Ede) mown meadow

"The meadow mown three days ago (by Ede)"

b. Die seit drei Tagen (*von Ede) gemähte

Wiese (POST)

The since three days (*by Ede) mown meadow

"The meadow that has been mown for three days (*by Ede)"

Despite having the same morphological representation, the LF of the participle in the two constructions must be totally different.

(Stechow, 1999b) argues that the LF of the attribute in (17 a) must be at least as complicated as the following expression

![]()

Perfect aspect: In (13), the participle head contains the information that (Klein, 1994) calls the PERFECT aspekt - the localisation of the event before the reference time. Following Klein, many researchers call relations that are bound to an event aspects. We speak of aspect relations. These days, in addition to the aforementioned perfect aspect, the relation e Í t (with t as reference time) is often called PERFECTIVE (cf. e.g. (Musan, 2001)). As the slavic perfective morphology, according to (Verkuyl, 1972, Verkuyl, 1988), (Krifka, 1989), (Schoorlemmer, 1995) and many others, primarily encodes the telicity of the VP, i.e. the lack of a subinterval feature in the sense in which this term is used by (Dowty, 1979), a more neutral term is required. In agreement with (Klein, 1994), we intend to use the terms INCLUDED and POST for the relations "part of" and "<".

(Paslawska and Stechow, 2001) demonstrate that perfective VPs in Russian and Ukrainian are localised by means of either the aspect relation INCLUDED or the aspect relation POST. This leads to multiple meanings for preterite and future statements (Maslov's "Implizites Plusquamperfekt" (1987)):

(14) Masha vyshla v vosem?

chasov (russ. )

M.

go-pfv-pret at 8 o'clock

(14a) PAST*i at 8(i) INCLUDED(i)(e) Masha goes(e) ("she went")

(14b) PAST*i POST(i)(e) at 8(e) Masha goes(e) ("she had gone")

(15) V vosem? chasov, Masha

uedet (russ. )

At 8

o'clock Mascha go-pfv-pres

"She will

go/will have gone at 8."

(16) Kogda ty priedesh?, on uzhe

uedet (Maslov, 1987: p. 200 f.)

When you

come-pfv-pres, he already go-pfv-pres

"When you come, he

will already have gone."

In Hungarian, the relationships are very similar to those in Russian and Ukrainian.

In the ensuing phase of the project, data from a variety of

languages will be researched so that the theory proposed can be further

developed on the basis of these data. The project will design a

catalogue of questions on the data pertaining to the perfect. By

answering these questions, it should be possible to establish the

tense/aspect system of the individual languages investigated, at least

as a first approximation. One of the aims of this is to extend the

tense/aspect typology.

A.2 Adverbials

A.2.1 Quantifying temporal PPs

The semantics for temporal adverbs that has to date been developed in

the literature on tense is exclusively intersective. Thus, a sentence

like Fritz rief am Montag an ("Fritz phoned on Monday") is interpreted

as:

![]()

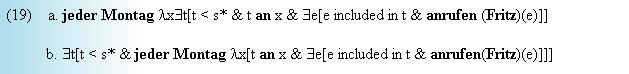

Here, the temporal adverb am Montag is connected subjunctively with the Tempuszeit. (Ogihara, 1995b) points out that this formalisation for quantifying temporal PPs creates a scope paradox:

(18) Fritz rief an jedem Montag an

Fritz phoned on every Monday up

"Fritz phoned every Monday."

The temporal quantifier jeder Montag can have wide or narrow scope with respect to the semantic past tense:

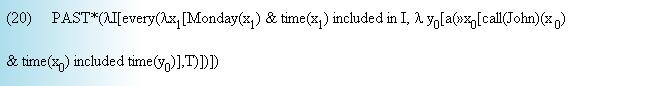

The LF (19a) implies that jeder Montag contains a time before the speech time; (19b) says that there is certain past time in each Monday. (Heim, 1997) maintains the view that the first LF is correct if one can establish by means of a presuppositional theory for the tense that jeder is only defined for Mondays in the past. Ogihara did not manage to present a usable solution to the problem in the aforementioned paper. In most of the literature on temporal adverbs, the problem is not even discussed; in other relevant literature, it is not sytematically solved; this also applies to such broadly based investigations as (Ernst, 1998) or (Musan, 2000). The theory presented by (Pratt and Francez, 2001), who investigate cascades of temporal PPs with quantifiers, represents an advance in this area. The approach they take assumes that the basic problem with all existing approaches lies in the intersective interpretation of temporal PPs in line with (Dowty, 1979). They claim that a temporal PP with a generalised quantifier in the object position always limits the quantifier. (Pratt and Francez, 2001) would analyse the sentence in question as:

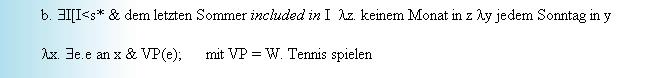

A crucial idea of this approach is that temporal quantifiers are relativised to a time that can be bound via a higher temporal operator. The formula involves I, which localises the time of Monday. The fact that temporal quantifiers have to contain a time variable capable of being bound is an idea that has cropped up many times in the literature; not only in the aforementioned papers by Ernst and Musan, but also in (Stechow, 1991). When one analyses the formula in (Pratt and Francez, 2001) more closely, one sees that it is not correct that the PP restricts the quantifier. The contribution that the preposition an makes is reflected in the statement time(x0) included in time(y0), which belongs to the nucleus of the quantifier, not to the restriction. Pratt & Francez' relatively non-transparent theory is that temporal quantifiers are systematically quantified into a PP in the sense of (Heim and Kratzer, 1998: 197f.). The PP itself is, of course, connected with the VP or another phrase subjunctively. This is, at any rate, the working hypothesis of this project. In the case of cascades of temporal PPs, this hypothesis leads to unexpected 'inverse linking' structures that, to the best of our knowledge, have not yet been proposed in the literature on tense (cf. (May, 1977, May, 1985)). This is illustrated in the following sentence:

(21)

a. Wolfgang hat im letzten Sommer in keinem

Monat an jedem Sonntag Tennis gespielt

Wolfgang has in-the last summer in no month on every Sunday tennis

played

"For no month last summer did Wolfgang play tennis every Sunday."

The D-structure is obtained by reconstructing the quantifiers in the position of their trace:

(22) Wolfgang an jedem Sonntag in keinem Monat in

dem letzten Sommer Tennis gespielt hat

Wolfgang on

every Sunday in no month in the last summer tennis played has

The D-structure is obtained by pied-piping the preposition in question during the QR process. It should be obvious that these truth conditions cannot be obtained by means of the intersection rule stemming from Dowty, which interprets VP projections as blocks of time that are disected by the adverbial.

The idea outlined here raises interesting questions. One of these is the relationship between D-structure/S-structure and LF. It is absolutely impossible for (22) to be understood as the reading (21a) if (22) is interpreted as the S-structure. Thus, the restrictions that apply to scrambling are different from those that apply to QR, and obviously fewer restrictions apply to scrambling with pied-piping than without. Languages like Hungarian, which, with its multiple topicalisation (cf. (Kiss, 1987)), makes use of movement rules that are comparable to German scrambling, reveal the same surface order of quantified adverbials and can be analysed analogously:

(23) Hungarian

Wolfgang

múlt

nyár-on egyik

hónap-ban sem

teniszez-ett minden

vasár-nap

W. previous summer-in any month-in also-not play-tennis-pret. every

Sunday-Nom

Positional languages like Italian and English, which reveal the same sequence of adverbials as German - but in postverbal position - present a real challenge.

(24) Italian

L'estate scorsa Mario non ha giocato a tennis in

nessun mese ogni domenica

In the last summer Mario not has played tennis in no month

on every Sunday

Actually, one would expect to see a mirror-image sequence of adverbials in this case. Here we come up against the problems of adverbial syntax, known since (Cinque, 1999), (Pesetsky, 1995) and (Ernst, 1998), which are still waiting for a generally accepted solution but which must be approached here from the semantic side. These issues of logical syntax must be resolved in cooperation with Project B12 (Stechow/Sternefeld). Italian and Russian immediately raise the question as to an appropriate interpretation of negation and NPI quantifiers, such as nessuno (cf. (Penka and Stechow, 2001)).

As far as we know, there have been to date no systematic

investigations into quantifying temporal PPs. This project will look

for and systematically collect data on this phenomenon from corpora. A

systematic handling of this neglected area is obviously of the utmost

importance for the architecture of the T/A system.

A.2.2 Embedded Adverbs

It is important to differentiate between movable and non-movable

indexical embedded adverbs. In new papers (e.g. (Schlenker, 2001)) on

this subject, the difference between anaphoric and deictic (or context

dependent) adverbs is referred to. 'The day after tomorrow' and 'in two

days' are syonymous in extensional contexts:

(25) Peter will leave the day after tomorrow

(26) Peter will leave in two days

But this does not apply to intensional contexts:

(27) a. ??Peter has told me repeatedly over the years that he would leave the day after tomorrow

b. Peter has told me repeatedly over the years that he would leave in two days

The classical explanation ((Kaplan, 1979), (Dowty, 1979)) is that adverbs like 'yesterday' are deictic; that is, they get their reference from the speech context, but this is too strong for (27b). We will investigate how much a context theory can deliver here.

Generally speaking, this project is interested in indexical impressions in embedded contexts, as well as the disparity between syntactic and semantic relationships in attitude contexts. This disparity is a problem for Schlenker's analysis:

(28) I thought I was you

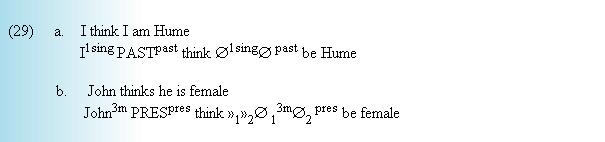

Is will also be interesting to generalise Kratzer's hypothesis that de se tenses and pronouns are always zero tenses/pronouns:

The congruence relationships are marked by the exponents. The question as to why zero pronouns are sometimes realised and sometimes not is still unanswered:

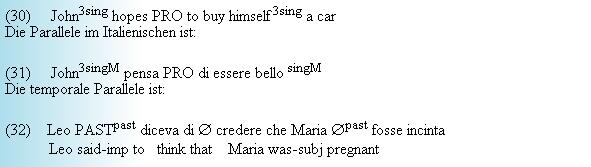

The transmission of the features requires an explanation: PRO transmits the features without having them itself.

What is unexpected is the observation that deictic adverbs can be sensitive to the tense of the verb:

(33) a. In two days John will believe that Peter left a day earlier

b. ??In two days John will believe that Peter left tomorrow

This problem points to the as yet not fully understood interaction between deictic adverbs and relative tenses. These facts, which were first noted by Wurmbrand, should be investigated in the next phase of the SFB.

Embedding under modals is also interesting:

(34) a. It might be 9 PM

b. It might have been 9 PM

and the contrast with

(35) a. John believes that it's 9 PM

b. John believes that it might be 9 pm

The syntax is not clear here. Is this a case of subjective modality? What would be the difference then between (34) and (35)?

This project is involved in intensive cooperation with leading

experts in the semantics of attitudes. In a lecture (Discussion about

Monsters (with David Kaplan and Philippe Schlenker), Lecture at UCLA,

Los Angeles (USA), 2001), Stechow combined Schlenker's theory with the

classical theory by Kaplan and discussed this with Kaplan and

Schlenker. The results are directly relevant to the questions raised

here and should be incorporated into the work in the next phase of the

project.

A.3 Aspect Theory

Aspect Relations

The insight that aspect morphology, as a general rule, encodes not only

an aspect class but also an aspect relation, and this not in an

unambiguous way, is important for a successful system of aspect

semantics. Thus, the perfective morphology in Russian and Ukrainian,

for example, selects the telicity of the VP and at the same time checks

whether the aspect relation is INCLUDED or POST (cf. (Paslawska and

Stechow, 2001)). The choice of the first relation results in an AORIST,

while the choice of the second relation results in a PERFECT, which are

here taken to be semantic terms that encode an interplay between aspect

relation and aspect class, i.e. something semantically complex. This

view is a synthesis of ideas from Dowty and Klein, who are

representative of many other researchers. The results and architecture

of the aspect theory have already been presented in detail in section

A1.

(36) a. *Der Aufsatz

ist immer noch abgegeben

The essay is always still handed-in

"*The essay is still handed in."

b. Das Geschäft ist immer noch

geöffnet

The shop is always still opened

"The shop is still open."

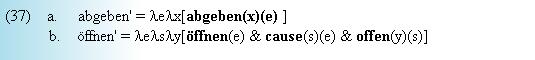

This contrast is explained by assuming two different lexical entries for abgeben and öffnen, namely:

The implementation of the adjectival passive is now possible only with the help of different stativisers:

(38) a. pres[POST[the essay handed-in]] (is)

b. pres[RESULT[the shop open]] (is)

The unacceptability of modifying the first sentence with noch immer results from the fact that an POST-state - Parsons' (1990) "resultant state" - can never end, while this is naturally possible for a qualitatively described state - Parsons' "target state".

This type of analysis is adopted in (Alexiadou and

Anagnostopoulou, 2001) and (Anagnostopoulou, 2001), for example. They

do not take into consideration the Aktionsarten, i.e. the internal

construction of the VP with aspect operators. It has been known since

(Verkuyl, 1972, Verkuyl, 1988) that the choice of the object plays a

role in determining the aspect class. One of the few compositional

theories for this phenomenon is the aforementioned one by Krifka. It is

not at all clear how this can be reconciled with Kratzer's verbal

semantics for two-state verbs.

A.4 Result Modifiers

Katzer's RESULT operator considers states to be basic terms. This

raises the question as to the localisation of states in time, which is

discussed in detail in (Herweg, 1990: 3.2) on the basis of the

following sentence:

1.. Gestern war es kalt

Yesterday was it cold

"It was cold yesterday."

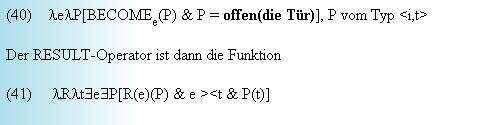

Gestern indicates the reference time r, while T(s) the time of the state kalt(s). If 'T(s) included in r' is true, the possibility that it is still kalt today is ruled out. If 'r included in T(s)' is true, an existential reading is ruled out. The DRT solves this problem with the stipulation that r and Ä(s) overlap; that is, it does not require a special aspect relation for states. (Herweg, 1990) and (Katz, 1995) advocate the hypothesis that the problem is best solved by treating states as properties of times. The sentence means then that there is a time in gestern at which it is kalt. Thus, the possibility that the state of being cold continues to exist is not ruled out. This is certainly the simplest solution. However, the definition of two-state verbs is then no longer meaningful because times are not caused by an event. It seems to make more sense to interpret states as properties of times and to define a verbal like die Tür öffnen ("open the door") as:

Thus, RESULT(die Tür öffnen) holds for a time if t borders on an event e which produces a P-result and P at t is true. An adverb like für zwei Stunden ("for two hours") modifies a relation between events and properties of times and is thus embedded under the RESULT operator. The formulation is almost identical with that given for verbs of change in (Stechow, 1996), with one important difference: here we have a two-place relation that allows compositional access to the resultant state, which was not possible before and which presented an unsolved problem in Stechow's earlier papers.

This approach also makes a representation of the restitutive reading of a wieder ("again") modification possible without further internal decomposition. The syntactic decomposition theory defended in (Stechow, 1996) has been criticised from time to time (e.g. in (Jäger and Blutner, 1999)) without a compositional alternative having been offered. In the approach introduced here, restitutive wieder can modify a two-state verb and characterise the resulting state as repetition alone. The feasibility of the restitutive reading is at the same time a test that separates two-state verbs from other Accomplishments/Achievements. For wieder modification, there are data in (Beck and Snyder, 2001) from various languages that should be drawn on and documented for this project.

A theory of this kind deserves to be developed further. As far

as empirical knowledge is concerned, this means that we must stay on

the lookout for further adverbs that behave like für zwei Stunden,

i.e. that are resultant result modifiers.

A.5 Tense under Subjunctive

The semantics of the subjunctive should be investigated here only in so

far as it is important for T/A semantics and context theory.

(Schlenker, 2000) was the first to observe that the subjunctive in

German cannot be used under verbs like glauben ("believe") or sagen

("say") if the verb is in first person singular, present tense.

(42) a. Der Peter

meint, es sei später, als es tatsächlich ist/*sei

The Peter thinks, it is-subj. later, than it actually is/*is-subj.

"Peter thinks it's later than it really is/*be."

b. Der Peter meint, es ist später, als es tatsächlich

ist/*sei

The Peter thinks, it is later, than it actually is/*is-subj.

"Peter thinks it's later than it really is/*be."

(43) a. Ich glaube, dass

Maria krank ist/*sei.

I believe, that Maria sick is/*is-subj.

"I believe that Maria is/*be sick."

b. Ich behaupte, dass Maria krank ist/*sei

I claim, that Maria sick is/*is-subj.

"I claim that Maria is/*be sick."

(44) a. Peter

glaubt, dass Maria krank ist/sei.

Peter believes, that Maria sick is/is-subj.

"Peter believes that Maria is/be sick.

b. Peter weiß, dass Maria krank ist/*sei

Peter knows, that Maria sick is/*is-subj.

"Peter knows that Maria is/*be sick."

Schlenker advocates the theory that tense behaves exactly like

a logophoric pronoun under the present subjunctive. Logophoric pronouns

are obligatorily moved under certain verbs of attitude and speech

rendition and convey that the subject views the content of the attitude

'de se', i.e. uses the pronoun 'ich' ("I"), for example (Meine Hosen

brennen ("my pants are on fire") vs. Seine Hosen brennen ("his pants

are on fire")). Logophoric elements must never refer to the speaker

herself. Schlenker uses these facts to support his context theory,

which is briefly described at another point. For the embedded tense,

the 'amount of context' of the subject as defined by (Stalnaker, 1984)

is the decisive factor in checking the logophoric elements. An

appropriate theory of subordination cannot afford to pass over these

facts. The facts show that the semantics of the tense cannot be treated

independently from the semantics of the modals. This is a problem for

standard theories, which quantify separately over worlds and times,

while for Schlenker it is evidence that, in the case of verbs of

attitude, quantification must be carried out globally over contexts.

This highly demanding topic is being handled by Fabrizio Arosio within

the framework of his dissertation.

A.6 Typology

A.6.1 T/A Typology

The T/A typology is being developed in accordance with the previous

guidelines.

A.6.2 Typology of Stativisers

The operators RESULT and POST introduced in section A.1 form the

semantic core of the 'adjectival passive'. These constructions are

adjectival in German and English but not, for example, in modern

Greek:

(45) a. *Der Aufsatz

ist von Monika abgegeben (Rapp, 1998a)

The essay is by Monika handed-in

"*The essay is handed in by Monika."

b. mod. Gr. To

vivlio ine grameno apo ti Maria

The book is written by Maria

(46) pres [PartP PERFECT [[VoiceP agent(e)(x) & [PartP to vivlio grammeno]] [x apo ti Maria]]]

The impossibilty in German of nominating an agent can be formulated as a language-specific selection restriction: in German, the result operator selects a non-agentive VP. In Kratzer's theory (cf. (Kratzer, 1994)), which we adopt, a telic VP has no agentive argument. This is introduced by means of a separate projection voice in the syntax. The aforementioned language distinction can now be explained by saying that in modern Greek, in contrast to German, the stativisers are above VoiceP.

Thus, we are now faced with the task of developing a typology

of adjectival perfect participles that can be cross-classified

according to the properties selected VP/selected VoiceP.

A.6.3 Typology: Tense in Relative Clauses and Complement Clauses

A comparison of English, Japanese and Russian suffices to show that an

expressive typology for tense in relative and complement clauses must

distinguish between the following points for individual tenses: (a) Is

an absolute interpretation of the tense possible? (b) Is an

anaphoric/bound reading possible? (c) Is a relative interpretation

possible? In English, three basic constellations are possible:

absolute, anaphoric and relative interpretation. These three

possibilities exist for the adjunct, but for complement clauses there

is no absolute reading.

For English, Japanese and Russian, the tense typology is as

follows:

Für das Englische, Japanische und Russische sieht die

Tempustypologie folgendermaßen aus:

absolute, relative, *anaphoric

*absolute, relative, *anaphoric

Russian

absolute, *relative, anaphoric

*absolute, relative, *anaphoric

In detail, the relationships are substantially more

complicated than this. But even with these coarse characteristics, we

can develop an insightful typology that extends beyond what is already

known.

A.6.4 LF-Typology

Each data entry in the FileMaker database will contain a reference to

the relevant structure; this will make the database an interesting

instrument for the practical work of linguistics. Thus, an LF typology

is involved. For Russian, it would, for example, be necessary to point

out that a simple perfective sentence in the preterite, such as Masha

vyshla ?M. ging-pfv?, can have three different LFs: aorist, pluperfect,

perfect of result:

(47) Russian: Masha vyshla

a. Aorist: [TP PAST past [AspP INCLUDED pfv [VP Masha vyshla]]]

b. Pluperfect: [TP PAST past [AspP POST pfv [VP Masha vyshla]]]

c. Perfect of result: [TP PRES past [AspP RESULT pfv [VP Masha vyshla]]]

(48) German: Manfred ist eingenickt

Manfred has nodded-off

"Manfred has nodded off."

a. Present perfect: [TP PRES pres [AuxP POST has [PartP Manfred nodded-off]]]

b. Perfect of result: [TP PRES pres [AuxP has [PartPRESULTAT [VP Manfred nodded-off]]]]

The references to the type of a construction are made via a

relational field. As the analyses are controversial in every case,

possible alternatives are provided. Furthermore, the entries are

updated in line with advances in knowledge. As this occurs globally,

the individual data entries do not need to be revised. Thus, the LF

corresponding to the current state of research can in principle be

obtained for every entry.

B. Investigations Based on Data

B.1 The T/A Archive: The FileMaker Database

The Filemaker Database contains approx. 1200 data from the languages

under investigation (so far ancient Greek, German, English, Italian,

Japanese, Latin, Swedish, Russian, Ukrainian). The base contains data

from various sources: from linguistic literature (the most important

examples coming from the "classics" of the literature on tense), from

documentary evidence and from surveys (introspective data).

The data are presented in the original script and in transcription, with an English glossary and translated into English. They are analysed according to various categories (e.g. according to relevant grammatical categories and subordination relationships). The documented examples also contain an indication as to the source, which refers to a separate literature database from which the precise source can be obtained. The analysis allows a specific search for similar phenomena in a variety of languages and makes the discovery of typological regularities easier.

As the data are recorded and characterised in such a way as to be as neutral as possible with respect to different theories, the database is, in addition to its primary function as an archive of examples, also intended to be accessible to a wider public, for instance language teachers, as a tool for investigating the phenomena treated. For this purpose, the database is also available on the Internet with the help of a web interface (http://134.2.147.30/Standard.htm). The web access is already functioning, although its functional scope will be considerably expanded in the near future. Selected data in analysed form can be transferred from the Internet to a Word document, where they are then able to be used directly as documentary evidence.

When doing the theoretical work of the project, it has been

proven to be extremely helpful and practical to have the File-Maker

database handy as a kind of on-line file of documentary evidence. Now

the database is also being used by researchers outside the project, as

well as students, and not only to search for evidence, but also to send

us their examples, which we then add to the database. We will continue

to add to it in the second phase of the project; presumably we will

also continue to communicate with people outside the project, and in so

doing, we will be happy to respond to suggestions from external users

of the database regarding functional modifications and/or

extensions.

B.2 Annotated Speaker Intuitions: The Annotated Database

The main focus of the annotated database is embedded structures. Of

particular interest are the differences in interpretation between

temporal expressions in the scope of verbs of attitude versus those in

adjunct clauses, participial clauses and relative clauses. There is

significant interlingual variation. These differences, both syntactic

and semantic, are encoded in the annotated database. So far, the

database contains 220 complex sentences (110 with relative clauses, 110

with complement clauses) from 10 typologically unrelated languages; 11

different temporal relations are expressed. Moreover, the database also

has a query language. The method applied for the annotation of

clause-internal temporal relations favours no particular language or

theory and is easy to use, requiring no special training. The annotated

remarks come with a well-defined model-theoretical interpretation. Here

is an example of an annotated entry:

As can be seen from the diagram, relationships between the verbs in the annotated sentences are established via labelled directed edges indicating the temporal relation that the annotator assumes for the verbs. In the example given, the erinnern is after the sprechen and the fragen, while the fragen is part of the sprechen.

One of the tasks of the annotated database is to develop intuitive annotation for modifiers, and perfect structures are of particular interest here.

As the interpretation of temporal expressions is only partly determined by the grammar, Project B10 plans to investigate the lexical and structural preferences that are critical for an interpretation systematically and also statistically within the framework of the annotated databank. It may also be possible to train a statistical parser, or, in other words: the annotated corpus with its tree database could test statistical parsers. More precisely, the following is planned: verb-verb pairs will be extracted from corpora, and clustering techniques will be applied to determine which classes of verbs have which temporal relations to which other classes of verbs, and to determine which relation is intended in a given sentence. This should in turn be tested in comparison with performance. In order to obtain statistically significant statements, hand annotation is not practical because the amounts of data soon become too large. An automatic method is necessary, and we will use overt indicators for that. As an initial step, we are using the overt perfect marker have, and we are trying to deduce stereotypical relations that crop up again and again:

(49) a. John saw the girl he met at the party.

b. John saw the girl he had met at the party.

c. The girl who left the party early had eaten a big breakfast.

Natural order: eat < leave.

d. The girl who left the party early ate a big breakfast.

Natural order: leave < eat

Furthermore, it seems to make sense to compare annotated remarks. For this purpose, the annotated remarks include a well-defined model-theoretical interpretation. A pilot study on this topic is already underway: 250 sentences from the British National Corpus have been tested, and in doing so, lexical preferences were also taken into consideration.

Moreover, it is of vital importance for the

theoretical-typological goals of the project to continue running our

multilingual retrievable database and expanding it in the directions

outlined.

Methods

For the theory-related investigations, this project uses the methods of

the so-called Transparent Logical Form (=TLF), now favoured by numerous

semanticists (cf. e.g. (Stechow, 1996), (Beck, 1996) or (Heim and

Kratzer, 1998)). This theory adopts the customary architecture of

Generative Grammar, e.g. D-structure, S-structure, PF and LF. The

essentials of the LF in this approach are that it unambiguously fixes

the interpretation on the basis of context dependence, i.e. that, for

example, the scope of quantifiers is clearly encoded. Similarly to

Project B12 (Stechow/Sternefeld), the parameters on which the

interpretation is dependent, in particular world, time and event, are

explicitly represented by variables. One of the questions to be

investigated is whether or not the variables world and time can be

eliminated in favour of a single variable, the context variable. The

semantics is a model-theoretical possible worlds semantics in the style

of (Dowty, 1979).

The composition principles should be simple: functional application, intersection and lambda abstraction, as required in (Heim and Kratzer, 1998). The complications result from the lexical semantics and the localisation of meaning components on functional heads, which are normally determined by the morphology of the lexemes used.

It is not yet clear what the final format of the context theory will be.

The syntax of this project makes extensive use of functional categories, e.g. Voice, Aspect, Tense, in the style of (Giorgi and Pianesi, 1998) or (Kratzer, 1996).

The methods of the data-related investigations are described

in the previous sections.

Literaturangaben

Alexiadou, A., und Anagnostopoulou, E. 2001. Participial Constructions and Inchoative Formation. Vortrag auf der Konferenz Workshop on Participles, Tübingen.

Anagnostopoulou, E. 2001. On the Distinction between Verbal and Adjectival Passives; Evidence from Greek. Vortrag auf der Konferenz Workshop on Participles, Tübingen.

Bäuerle, R. 1979. Temporale Deixis - Temporale Frage. Tübingen: Narr.

Beck, S. 1996. Wh-constructions and transparent Logical Form. Tübingen: Philosophische Dissertation.

Beck, S., und Snyder, W. 2001. Complex Predicates and goal PPs: Evidence for a semantic parameter: Erscheint in: Proceedings of the Berkely Linguistic Society.

Cinque, G. 1999. Adverbs and Functional Heads, A Cross Linguistic Perspective: Oxford Studies in Comparative Syntax. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dowty, D. 1979. Word Meaning and Montague Grammar: Synthese Language Library. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Ernst, T. 1998. The Syntax of Adjuncts: Manuskript. New Brunswick: Rutgers University.

Giorgi, A., und Pianesi, F. 1998. Tense and Aspect: Oxford Studies in Comparative Syntax. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Glinz, H. 1968. Die innere Form des Deutschen. Eine neue deutsche Grammatik. Bern: Francke.

Heim, I., und Kratzer, A. 1998. Semantics in Generative Grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Herweg, M. 1990. Zeitaspekte. Die Bedeutung von Tempus, Aspekt und temporalen Konjunktionen. Wiesbaden: Deutscher Universitätsverlag.

Iatridou, S., und Izvorski, R. 1998. On the Morpho-Syntax of the Perfect and How it Relates to its Meaning: Manuskript, MIT.&Nbsp;

Jäger, G., und Blutner, R. 1999. Against Lexical Decomposition in Syntax. Vortrag auf der Konferenz IATL, Haifa.

Kamp, H., und Reyle, U. 1993. From Discourse to Logic. Dordrecht/London/Boston: Kluwer Academic Publisher.

Kaplan, D. 1979. On the Logic of Demonstratives. Journal of Philosophical Logic 8:81 - 98.

Katz, G. 1995. Stativity, Genericity, and Temporal Reference. University of Rochester: PhD Dissertation.

Katz, G., und Arosio, F. 2001. The Annotation of Temporal Information in Natural Language Sentences. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Toulouse.

Kiss, K. 1987. Configurationality in Hungarian. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Klein, W. 1994. Time in Language. London, New York: Routledge.

Kratzer, A. 1994. The Event Argument and the Semantics of Voice: Unpublished manuscript, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Kratzer, A. 1996. The Semantics of Inflectional Heads. Girona.

Kratzer, A. 2000. Building Statives. University of Massachusetts at Amherst: Berkeley Linguistic Society.

Krifka, M. 1989. Nominalreferenz und Zeitkonstitution: Studien zur Theoretischen Linguistik. München: Wilhelm Fink.

Maslov, J. S. 1987. Perfektnost'. In: Teorija funktionalnoj grammatiki. Vvedenije. Aspektual'nost'. Vremennaja lokalizovannost?. Taksis.,, Hrsg.: A. B. e. alii, 195-209. Leningrad: Nauka.

May, R. 1977. The Grammar of Quantification. MIT: Ph.D. Dissertation.

May, R. 1985. Logical Form. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

McCoard, R. W. 1978. The English Perfect: Tense Choice and Pragmatic Inferences. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Musan, R. 2000. The Semantics of Perfect Constructions and Temporal Adverbials in German. Humboldt Universität: Habilitationsschrift.

Musan, R. 2001. Seit-Adverbials in Perfect Constructions: Manuskript, Humboldt Universität Berlin.

Nedjalkov, V. P. 1988. The Typology of Resultative Constructions. In: The Typology of Resultative Constructions, Hrsgs.: V. P. Nedjalkov und S. J. Jaxontov, 2-62. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Ogihara, T. 1995b. Doubble-Access Sentences and Reference to States. Natural Language Semantics 3:177-210.

Parsons, T. 1990. Events in the Semantics of English. A Study in Subatomic Semantics. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Penka, D., und Stechow, A. v. 2001. Negative Indefinita unter Modalverben. Erscheint in Linguistische Berichte .

Pesetsky, D. 1995. Zero Syntax. Experiencers and Cascades . Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Pickbourn, J. 1798. A Dissertation of the English Verb: Principally intendeed to Ascertain the meaning of its Tenses.

Pratt, J., und Francez, N. 2001. Temporal Generalized Quantifiers. Lingistics and Philosophy 24:187-222.

Rapp, I. 1997. Partizipien und semantische Struktur: Studien zur deutschen Grammatik. Tübingen: Stauffenburg Verlag Brigitte Narr GmbH.

Rapp, I. 1998a. Fakultativität von Verbargumenten als Reflex der semantischen Struktur. Linguistische Berichte 172:490 - 529.

Rapp, I. 1998b. Zustand? Passiv? - Überlegungen zum sogenannten "Zustandspassiv". Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 15.2:231 - 265.

Rapp, I., und Stechow, A. v. 2000. Fast "almost" and the Visibility Parameter for Functional Adverbs. Journal of Semantics 16:149-204.

Schipporeit, L. 1971. Tenses and Time Phrases in Modern German . München: Max Hueber Verlag.

Schlenker, P. 2000. Propositional Attitudes and Indexicality: A Cross-Categorial Approach. MIT: Ph.D Dissertation.

Schlenker, P. 2001. A Plea for Monsters. Los Angeles: USC.

Schoorlemmer, M. 1995. Participial Passive and Aspect in Russian. Onderzoekintsituut vor Taal en Spraak. Utrecht University: PhD Dissertation.

Stalnaker, R. 1984. Inquiry. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press.

Stechow, A. v. 1991. Intensionale Semantik - Eingeführt anhand der Temporalität: Arbeitspapier der Fachgruppe Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Konstanz.

Stechow, A. v. 1996. The Different Readings of Wieder "Again": A Structural Account. Journal of Semantics 13:87-138.

Stechow, A. v. 1999b. German Participles II in Distributed Morphology. In: erscheint in: Proceedings of the Bergamo Conference on Tense and Mood Selection, Hrsgs.: J. Higginbotham, A. Giorgi und F. Pianesi. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stechow, A. v. 2001b. Perfect Tense and Perfect Aspect: Seit and Since. Vortrag auf der Konferenz Workshop on Participles, Tübingen.

Verkuyl, H. J. 1972. On the Compositional Nature of the Aspects. Foundations of Language. Supplementary Series. 15.

Verkuyl, H. J. 1988. Aspectual Asymmetry and Quantification. In: Temporalsemantik. Beiträge zur Linguistik der Zeitreferenz, Hrsgs.: V. Ehrich und H. Vater, 220-259. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Wunderlich, D. 1970. Tempus und Zeitreferenz im Deutschen . München: Max Hueber Verlag.

Annette Farhan. Last modified 14.05.2003; Translation by Angela Cook